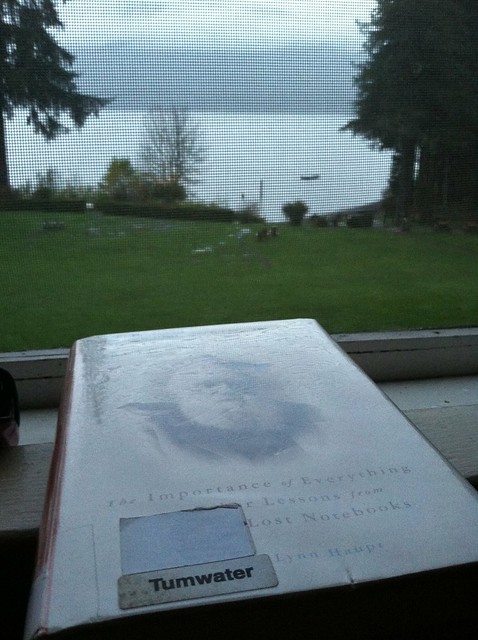

Today is the anniversary of the publication of The Origin of the Species, by Charles Darwin. As I regularly make it a practice to find good resources for my congregation and put them into calendars that mark dates like these, last month I checked out a bunch of Darwin books from the library. Many I was already familiar with (One Beetle Too Many and The Humblebee Hunter are my favorite picture books, and I really like the YA novel Charles and Emma: The Darwins' Leap of Faith), but I also received a stack I had not read before and I had to choose just one as I didn't have time for them all. My choice was a fortuitous one, and I am happy to say that Pilgrim on the Great Bird Continent: The Importance of Everything and Other Lessons from Darwin's Lost Notebooks by Lyanda Lynn Haupt is a most fascinating book.

Unlike other books about Darwin that I have read, this book focuses on the inner journey and his growth as a naturalist through the daily writings he kept on his trip aboard the Beagle. Haupt is herself a student of ornithology, so she admits to focusing on his work with birds mainly because that was the part that interested her the most, but also because she thinks birds are one of the more accessible areas of nature study for the general public. As I also like to casually watch birds, I found myself agreeing with her.

While there is a great deal of interesting science and history here, in the end it wasn't the science or the history of the book that was the real take-away for me. Haupt describes what she calls "the faith of a naturalist" and uses examples from Darwin and from her own life and studies as well as a few interviews she conducts that were in some way related to her topic. She weaves between the historical and the modern, the scientific and the philosophical, and it was a lovely and thought-provoking progression.

A few quotes:

In our own lives as homespun naturalists, the moments we do manage to spend becoming educated by our native places can wend their way into our daily lives, making it more and more difficult to see ourselves as individuals, self-sufficient and cordoned off somehow from our humus-y ground. We begin to see, rather, our lives as embodied, unseparate, inseparable, rushing forward with the whole of wild life.

****************

Yet it is here, in the spaces between what can be seen and what can be spoken, that the naturalist's faith often lies. This is why it is called faith. Intimacy, residence, patience, a sense of dwelling alongside wild nature, earthen insight, gratitude, affection, kindness, a kind of grace, a kind of joy - all of these unutterable things find a place in the naturalist's task.